The paintings are astounding. The interpretation less so. It’s a great shame that I’ve had to go to Wikipedia to find out what the National Gallery information cards didn’t tell me — this American artist was a great marine watercolourist.

Like the Tate the information cards have a problem — they determinedly point out every instance of racism, colonialism, oppressive suggestive, the misuse and portrayal of black and brown bodies and yet they just stay there, missing out the why. I’ve got no problem with these issues being mentioned — but it’s statements (a bit like being repeatedly hit over the head) rather than interpretation. For example, in a horrible picture of a man facing the fate of death by shark, an opportunity is shockingly missed to link this work to a work by Turner showing the offensive murder of enslaved people by drowning them as a disposable unwanted cargo, some of whom are consumed by sharks. Homer’s sailor does seem to be passively awaiting his fate — death by typhoon or shark, on a boat laden with sugar cane.

Yet these paintings do need interpretation, Homer determinedly resisted saying why, with quite comical retorts. Young ladies being respectable looking at respectable and suitable things — hilarious! This beach scene is so staged, it’s humourous as the correct young ladies are posing away like mad, with proudly lifted heads.

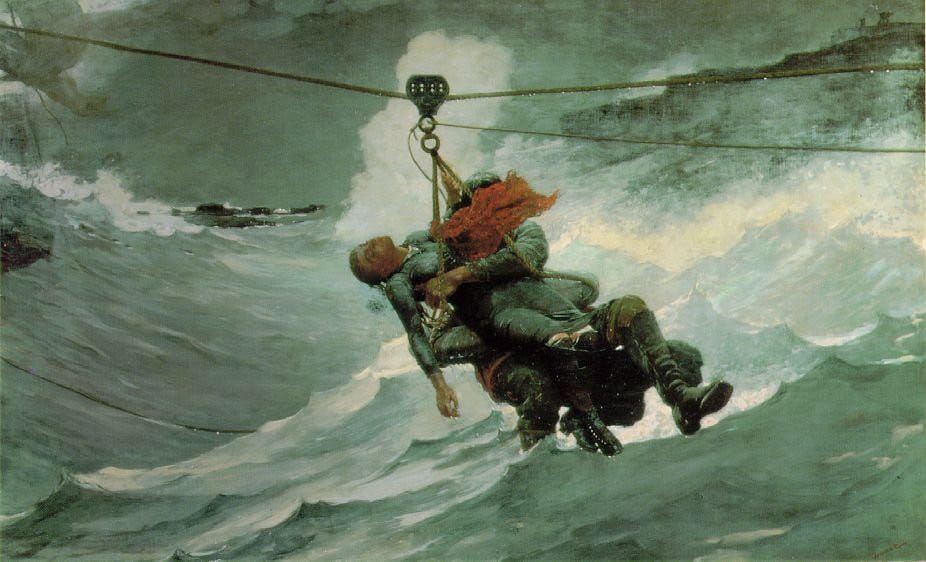

A rescue is condemned roundly by the information card for its anti-feminism — look at the female passivity it positively screams next to the painting. And yet this is almost Pointillism, look at this Seurat moment. Ordinary men have become like living Greek statues striding out of the sea, with their catch. Alarmingly a woman is being grasped by the hand, but her bathing clothes are probably so heavy and many women didn’t really swim then, only dip.

Equally shocking to his audience was another bathing scene. What leaps out is the modernity — they could almost be wearing trainers, Birkenstocks and lounge wear.

His seascapes feel touchable, feelable, almost smellable. He experiments with Grisaille, an emotionally connecting night silhouette of the coast. One marine scene offers hope of a brave new world post American Civil War, as the yacht moves forward through tossing seas. It’s the wonderful movement with the details of the larger ship in the background, which could be commercial or military….

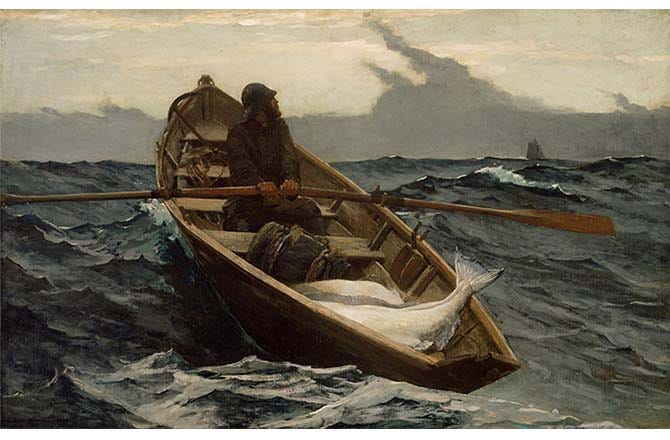

This made me laugh — the man facing the storm with fish as big as him!

There is also the romantic and the incredibly poignant — what has changed?

His natural history is a bit strange and also very painting en plein air — he has a before and after photo of a bird being shot by a hidden hunter; of a boy catching a valuable deer in a river — it’s ok he’s not drowning it, merely bringing back his catch. He paints a shiny fish in a very unshiny matte way. It is weird, but it made me think of Manet’s enjoyment of early cinematography. Homer is trying to be a movie camera here! (though it is weird at the same time — he often hides details very far away and the viewer has to work hard to work out what is going on).

Most thrillingly of all, Homer came to Tyne and Wear and celebrated working class men and women. I love it! It’s almost a Socialist Russian propaganda poster before Stalin and Lenin had even been thought of — the drama and dignity of the working woman….Indominatable! and triumphant in hardship.

More dramatically portrayed here, but the way the wind whips the child’s hair and still the woman goes on, unredoutable. If you look closely at his seascape rocks, there are bubbles on water, limpets, molluscs — the detail is incredible and beautiful.

It’s hard to tell without the information card, but the jacket tossed on the ground is a military jacket. This is restoration after war, peace after bloodshed, a restoration of things…. It also made me think — who would have done this task pre-war?

This portrait of Tyne and Wear fishermen makes me think of Munch’s dream like paintings….True proletarian dignity and heroism here. Similarly there is another of fishermen or lifeboat men about to head out into the storm — the hope, thoughts, trepidation, prayers are all there — it’s beautiful.

He’s also attempting the impossible — dramatic at sea rescues, almost photography in paint….

And the poignant, in much colonised Nassau, a boy looks pointedly at a walled off house. Who is the invader, the unwanted, who trespasses and who should be there? The walls are topped with glass, a practice still used today. It’s a subtle painting and yet the waiting boy’s tattered rags suggest that colonialism is not all beneficence. Similarly abandoned cannons dot the sandy shore of another sailing painting as another colonial administration takes over. Perhaps rather than fetishing brown bodies, he simply shows brown bodies at work, trying to start a tourist trade, to keep a fishing trade going, at work and rest.

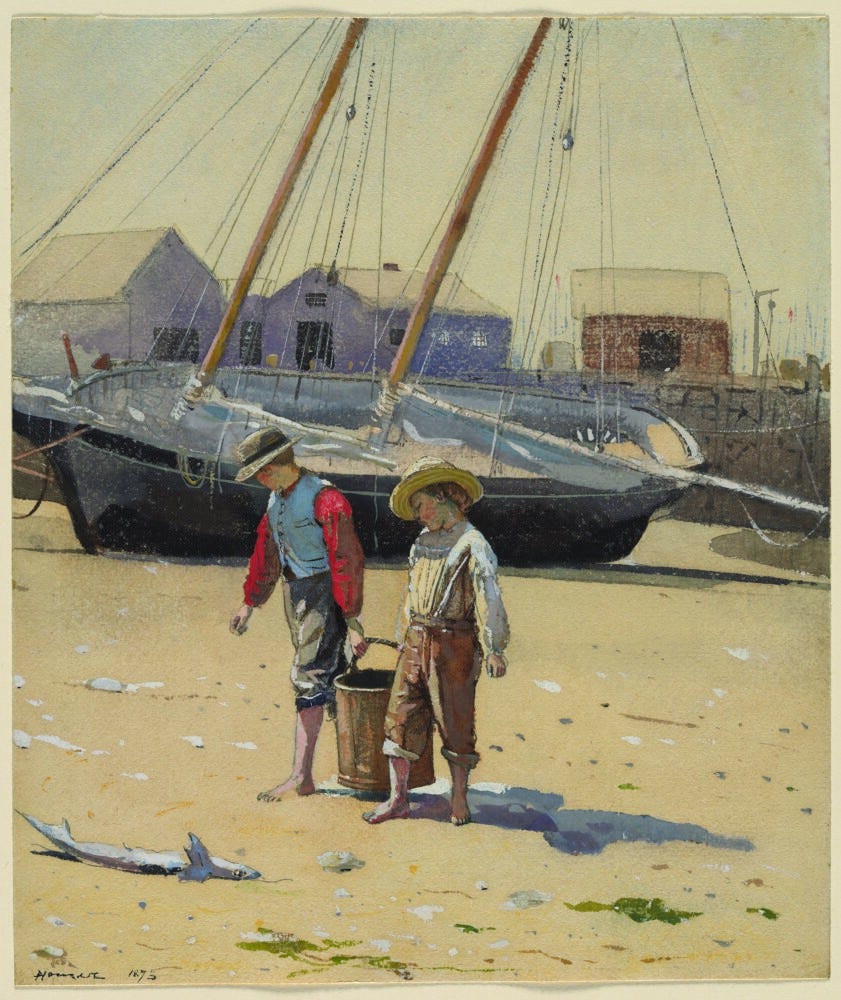

Ditto the boys in activities photos — taking eggs from cliff side nests or surprised/distracted/interested by a shark on the way across a beach. Perhaps there is nothing sinister here — these are just boyhood activities, along with the children at play and at work. They are just children being curious and somewhat destructive (with the birds eggs).

Interestingly he doesn’t portray black and brown people in distorted racist ways. Here in a celebration of freedom, the figures have regular features — not exaggerated, nor are they shown as foolish, exotically other or lesser, but in a Renaissance tableaux style. Dignity and hope is the order of the day, although they are romanticised at the same time. Are things changing he keeps asking in his subjects? I love the sweetness and naturalness of the smallest child and the nobleness (although still very real) of the boy looking to the side, ahead into a better future.

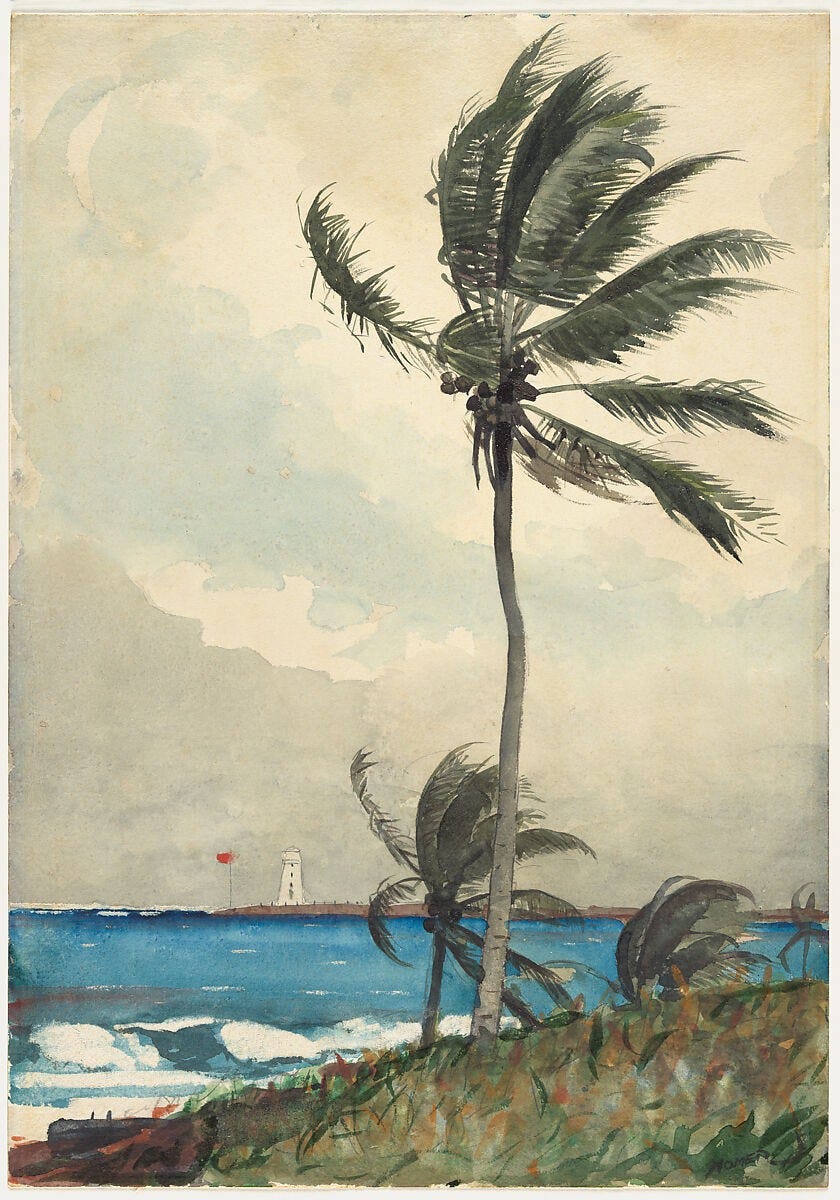

His palm trees are astounding, bobbing in the wind! The delicacy and movement.

What I really wanted to know was how his Civil War paintings compared to photography being used at the same time. Did they influence each other? Did he stage as much as battlefield photographers did? How did the Northumberland (Tyne and Wear) communities feel about the arrival of this American artist in their midst? Did they embrace him or regard him with suspicion? How did they change each other? Whilst eluding interpretation, he’s so much about connection. He wants us to connect with the beauty and life of seascapes, to admire and appreciate the hard graft of working class coastal communities, to admire their bravery and gutsiness, to consider the tourism of Nassau and the humanity of those in colonial territories, to think about the impact of Civil War and social change, to wonder…And wonder we do, such as at the Impressionist painting of brilliant flowers before a ridged rooftop gleaming, and designed to catch rainwater.

But it is a shame I had to leave a gallery and go to Wikipedia to learn more about the man and his wider role in the artistic world. Winslow Homer - Wikipedia

@ Paintings are not the author’s own, are from the Wilnslow Homer: Force of Nature exhibition and used purely to illustrate the National Gallery London’s exhibition, January 2023